Why passwords get hacked more often than people expect

Passwords are still the most common way people protect online accounts. They are also the most frequently broken security control. When people ask why passwords get hacked, the answer is rarely a single mistake or a single attack. Most compromises happen because passwords are easy to steal, easy to reuse, and easy to exploit at scale.

In practice, attackers do not need to “crack” passwords in the dramatic sense people imagine. They rely on leaked databases, automated login attempts, phishing messages, and infected devices. These methods succeed even when services follow basic security standards, because the password itself is a fragile secret that must be typed, remembered, transmitted, and stored.

The core problem is structural. A password is a shared secret between a human and a system. Once that secret is exposed anywhere—on another site, in a breach, or on a compromised device—it can often be reused without resistance. This is why many account takeovers happen without exploiting software bugs or advanced hacking techniques.

This article explains the most common and realistic reasons passwords get hacked today. It focuses on how attackers actually work, where defenses fail, and why passwords continue to be a weak foundation for account security, even when users “do everything right.”

Why passwords get hacked more often than people expect

Many people assume passwords get hacked only when someone is careless or when a service is badly built. In reality, passwords fail far more often because they are exposed indirectly. Attackers do not need to target a specific person or system. They work at scale and wait for normal behavior to do the rest.

The modern internet runs on shared credentials. People reuse passwords across work tools, personal email, shopping sites, and old accounts they no longer remember. When just one of those services leaks data, the same password often unlocks many others. From the attacker’s perspective, this turns random breaches into predictable success.

Another reason passwords get hacked so frequently is automation. Login attempts are no longer manual. Attackers test millions of credentials per hour using scripts and botnets. Even a very low success rate is profitable when repeated across thousands of services.

Security controls often assume that the password is secret and temporary. In practice, passwords live for years. They are typed on multiple devices, stored in browsers, synced to cloud accounts, and occasionally sent through email or chat. Each step increases exposure without the user realizing it.

The result is that password compromise is not an edge case. It is a normal outcome of how passwords are used and reused on the modern web.

Common expectations vs real-world password risk

| Common belief | What actually happens |

|---|---|

| “Hackers guess passwords one by one” | Most attacks reuse leaked credentials at scale |

| “Only weak passwords get hacked” | Strong passwords fail when reused or phished |

| “My account isn’t valuable” | Automated attacks target everyone equally |

| “No breach means no risk” | Old breaches still fuel new attacks |

| “Security tools stop most attacks” | Many attacks succeed before alerts trigger |

This gap between expectation and reality explains why password breaches feel sudden and personal, even though they follow well-known patterns.

Weak and reused passwords as the root cause of most breaches

When security teams analyze real-world incidents, one pattern appears repeatedly: weak or reused passwords. This is not because people are careless, but because password creation conflicts with how humans naturally think and work. Remembering dozens of unique, complex passwords is unrealistic without dedicated tools.

Password reuse is especially dangerous. A password does not need to be guessed or cracked if it already exists in a leaked database. Attackers buy, trade, and reuse credential dumps from breaches that may be years old. If a password was ever reused, it is effectively public forever.

Weak passwords worsen the problem, but they are not the primary driver. Even long, complex passwords fail once they are reused. Strength matters only if the password is unique and never exposed elsewhere. In practice, uniqueness is far harder to maintain than complexity.

Organizational password policies often make this worse. Forced rotation, arbitrary character rules, and frequent resets encourage predictable patterns. Users respond by making small variations that attackers can easily anticipate.

Local-first password managers can reduce this risk by generating and storing unique credentials per site. Privacy-first tools such as Passary approach this problem by keeping vault data local rather than syncing secrets through centralized servers, reducing exposure paths if another service is breached.

Common password behaviors attackers rely on

- ×Reusing the same password across multiple services

- ×Making small variations (e.g., Password1, Password2)

- ×Choosing passwords based on names, dates, or patterns

- ×Saving passwords in browsers tied to cloud accounts

- ×Never changing passwords unless forced

Password strength vs real-world exposure

| Password characteristic | Helps against guessing | Helps against reuse attacks |

|---|---|---|

| Longer length | Yes | No |

| Random characters | Yes | No |

| Uniqueness per site | Limited | Yes |

| Frequent rotation | Sometimes | Rarely |

| Manager-generated | Yes | Yes |

This is why security guidance increasingly focuses on uniqueness rather than memorability. A reused password is not a secret—it is a shared key waiting to be tested elsewhere.

Credential stuffing attacks explain why one leak breaks many accounts

Credential stuffing is one of the main reasons people are surprised when multiple accounts are compromised at once. It does not involve guessing passwords or exploiting software flaws. Instead, attackers take known email-and-password pairs from previous breaches and automatically test them on other services.

This works because password reuse is common and predictable. If a user reused the same credentials on a forum, a shopping site, and an email account, a single breach can unlock all three. From the attacker’s point of view, this is efficient, cheap, and reliable.

Credential stuffing is almost entirely automated. Attackers use botnets, cloud servers, and headless browsers to spread login attempts across thousands of IP addresses. This allows them to bypass basic rate limits and avoid detection. Even a success rate well below one percent can yield thousands of valid logins.

Importantly, the targeted service may not be breached at all. Its systems can be fully patched and correctly configured. The failure occurs because the password itself has already been exposed elsewhere. This is why companies often say “we found no evidence of a breach” while users still lose accounts.

Once attackers gain access, they often move quickly. They change account details, extract stored data, or use the account as a stepping stone to reset passwords on more valuable services.

How credential stuffing works

- Obtain leaked credentials from past breaches

- Load credentials into automated tools

- Test logins across many services

- Capture successful logins

- Exploit or resell access

Signs you were hit

- ⚠️ Login alerts from unfamiliar locations

- ⚠️ Password reset emails you did not request

- ⚠️ Locked accounts after failed login attempts

- ⚠️ Successful logins without malware present

- ⚠️ Multiple services affected in a short time

Credential stuffing explains why password breaches feel contagious. The problem is not one weak site, but a shared secret being reused across many independent systems.

How phishing steals passwords without breaking any systems

Phishing is one of the most effective ways passwords get hacked because it avoids technical defenses entirely. Instead of attacking servers, attackers trick people into handing over their credentials voluntarily. No vulnerabilities need to be exploited, and no passwords need to be cracked.

Modern phishing rarely looks suspicious. Messages often appear to come from trusted services and reference real events such as security alerts, invoices, document shares, or login problems. Many phishing pages are visually identical to the real site and work on both desktop and mobile devices.

What makes phishing especially dangerous is that password strength does not matter. A long, random password offers no protection if it is typed into a fake login page. From the attacker’s perspective, phishing turns the user into the weakest link in an otherwise secure system.

Phishing is also fast. Credentials are often used immediately after capture to bypass detection, reset recovery details, or add new authentication methods. By the time a user realizes something is wrong, access may already be locked in.

Even security-aware users are vulnerable under the right conditions. Time pressure, device limitations, and realistic context all reduce the effectiveness of visual checks and caution.

Common delivery methods

- • Fake security or account warning emails

- • SMS messages claiming urgent account issues

- • Messaging app links posing as shared documents

- • Search ads leading to counterfeit login pages

- • QR codes redirecting to malicious sites

Why it succeeds

- Trust in brands: Users lower their guard

- Visual similarity: Fake sites look legitimate

- Urgency: People act before thinking

- Mobile: URLs are harder to inspect

- Password-only: No second factor to stop misuse

This is why phishing remains effective year after year. As long as passwords must be typed into web forms, attackers can create convincing places to steal them.

Data breaches and the long afterlife of leaked passwords

When people think about breaches, they usually imagine a single event with a clear end. In reality, a data breach is often the beginning of long-term risk. Once passwords are leaked, they rarely disappear. They circulate quietly through underground markets, private collections, and automated attack tools for years.

Many breaches expose more than just passwords. Email addresses, usernames, password hints, and metadata all increase the usefulness of leaked credentials. Even when passwords are hashed, weak hashing or outdated algorithms can allow attackers to recover large portions of them over time.

What makes this especially dangerous is delay. Users often do not change passwords immediately after a breach, or they change them only on the affected service. If the same password is used elsewhere, attackers can exploit it long after public attention fades.

Breaches also compound each other. Attackers merge multiple leaked datasets to build detailed profiles that improve success rates in future attacks. A password that survived one breach may still be exposed through correlation with others.

This is why “old” breaches are still relevant. From an attacker’s perspective, leaked passwords age slowly and retain value as long as password reuse exists.

What typically leaks

- • Email addresses and usernames

- • Password hashes (or plain text)

- • Password hints or security questions

- • Account creation dates

- • Linked accounts list

Why they stay useful

- • Reuse: Enables attacks on unrelated services

- • Delay: Extends the window of exploitation

- • Aggregation: Improves targeting accuracy

- • Cost: Old data is cheap to reuse

This long afterlife explains why people lose accounts even when they have not signed up for anything new or clicked suspicious links. The exposure often happened long ago, and the consequences arrive much later.

Check if your data has been exposed

Because hacks happen in the background, you often won't know you're at risk until it's too late. The industry standard tool Have I Been Pwned allows you to safely check if your email or phone number has appeared in known data breaches. It is the best first step to understanding your current exposure.

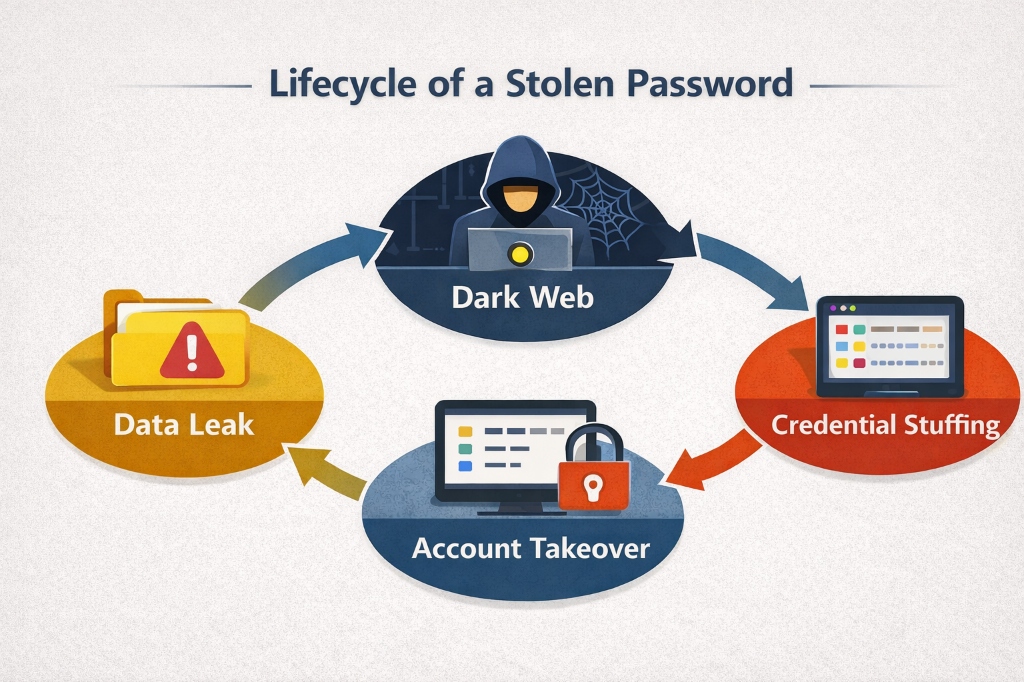

The invisible journey of a compromised credential

Brute force and password spraying still succeed at scale

Brute force attacks are often described as outdated, but they still work when basic protections are missing or misconfigured. These attacks rely on repeatedly trying passwords until one succeeds. While modern systems usually block pure brute force, many real-world environments still expose enough surface area for attackers to succeed.

Password spraying is a more subtle variation. Instead of trying many passwords on one account, attackers try a small set of common passwords across many accounts. This avoids lockouts and blends into normal login traffic. Spraying is especially effective against corporate, education, and government systems where default or weak passwords still exist.

These attacks succeed not because they are clever, but because they exploit scale and patience. A single failed login attempt looks harmless. Thousands spread over time and across IP addresses are harder to detect, especially on legacy systems or externally exposed services.

Cloud services, VPN gateways, email portals, and remote access tools are frequent targets. If rate limiting, monitoring, or account lockout policies are weak, attackers can keep trying indefinitely.

| Attack type | How it works | Why it succeeds |

|---|---|---|

| Brute force | Many passwords against one account | Weak rate limiting or no lockout |

| Password spraying | Few passwords across many accounts | Avoids detection and lockouts |

| Hybrid attacks | Small variations over time | Blends into normal traffic |

While these attacks are less glamorous than phishing or credential stuffing, they remain effective wherever password-based authentication is exposed without strong controls.

Malware and compromised devices bypass password security entirely

Malware changes the threat model completely. When a device is compromised, passwords no longer need to be guessed, reused, or phished. They can be captured directly at the moment they are typed, copied, or decrypted for use.

Keyloggers record keystrokes before encryption. Screen grabbers capture login flows visually. Browser malware can extract saved passwords, session cookies, and autofill data. In these cases, even a strong, unique password provides little protection because the attacker is observing legitimate use.

This is one reason people are sometimes hacked despite good password habits. The failure does not occur at the service level. It happens on the endpoint, where the password must exist in plain form for a brief moment so the user can authenticate.

Malware infections often come from common activities: installing unverified software, opening malicious attachments, using cracked applications, or running outdated operating systems. Once present, the malware may persist silently and harvest credentials over time.

Password managers help by reducing typing and limiting exposure, but they are not a full defense against a compromised device. This is why endpoint security, updates, and device hygiene matter as much as password practices.

Why insecure password storage amplifies breach damage

Not all breaches expose passwords in the same way. The impact depends heavily on how passwords are stored. When storage practices are weak, a single intrusion can turn into immediate, large-scale credential exposure.

Secure systems never store passwords in plain text. Instead, they store cryptographic hashes designed to be slow and resistant to guessing. When this is done correctly, stolen password databases are difficult and expensive to exploit. When it is done poorly, attackers can recover real passwords quickly and at scale.

The problem is inconsistency. Many systems still rely on outdated hashing algorithms, improper configurations, or shortcuts taken for performance reasons. In some cases, passwords are encrypted rather than hashed, which allows recovery if encryption keys are exposed. In the worst cases, passwords are logged, cached, or stored in plain text.

Once attackers obtain usable passwords, they do not need to attack the breached service again. The damage spreads outward through credential reuse, phishing, and resale. Poor storage practices effectively multiply the harm of every breach.

Local-first security designs reduce this risk by avoiding centralized password storage altogether. Keeping secrets encrypted on user-controlled devices limits how much damage a single server-side failure can cause.

- • Plain text storage (Critical)

- • Reversible encryption

- • Fast, unsalted hashing

- • Slow, salted hashing (Argon2, bcrypt)

- • Local-only isolated storage

- • Hardware-backed keys

Insecure storage does not just affect one service. It feeds the entire ecosystem of password abuse by supplying attackers with reusable secrets.

The absence of multi-factor authentication as a failure point

When passwords are the only line of defense, any exposure becomes a full compromise. This is why the absence of multi-factor authentication (MFA) is one of the most common failure points in real-world account takeovers. Once a password is stolen, nothing stops the attacker from logging in as the user.

MFA changes this dynamic by requiring something in addition to the password, such as a temporary code or a hardware-backed key. Even if a password is leaked through phishing, malware, or a breach, MFA can block access at the final step. Without it, every other control depends on the password remaining secret indefinitely.

Many users assume MFA is only necessary for “important” accounts. In practice, attackers often start with low-value services and move laterally. A compromised email account, for example, can be used to reset passwords elsewhere, making MFA absence on secondary accounts just as dangerous.

Implementation quality also matters. SMS-based MFA reduces risk but is vulnerable to SIM swapping and interception. App-based and hardware-backed methods provide stronger protection. However, the true modern answer is Passkeys. Passkeys replace passwords entirely with cryptographic keys stored on your device, making them phish-proof by design.

Local-first security tools often emphasize MFA and Passkeys not as optional features, but as necessary compensating controls for the structural weaknesses of passwords.

| Threat | Password Only | Password + MFA |

|---|---|---|

| Credential stuffing | Fails | Mostly blocked |

| Phishing | Fails | Often blocked |

| Brute force | Sometimes blocked | Strongly blocked |

| Malware on device | Fails | Often still fails |

| Server-side breaches | Fails | Limits reuse damage |

MFA does not make passwords safe, but it significantly reduces how often stolen passwords lead to real account compromise. Where MFA is absent, password failure is usually only a matter of time.

Why passwords keep failing despite better tools and policies

After decades of improvements, it is reasonable to ask why passwords still fail so often. The answer is not a lack of guidance or technology. It is that passwords are asked to do more than they are structurally capable of doing.

A password must be memorable, secret, reusable by the legitimate user, and unusable by anyone else. These requirements conflict. Any password that is easy to remember is easier to guess or reuse. Any password that is strong and unique is difficult to manage without tools. As a result, people and organizations make trade-offs that attackers reliably exploit.

Policies alone cannot fix this. Strong rules often backfire in practice, encouraging workarounds, reuse, and predictable patterns. Training helps, but it cannot eliminate phishing, malware, or breaches elsewhere on the internet. The problem persists even among highly technical users.

Better tools reduce risk but do not remove it. Password managers, MFA, and monitoring all help, yet the password remains a single shared secret at the center of authentication. As long as that secret must be typed and stored somewhere, it can be stolen.

This is why many security architectures now treat passwords as a legacy component to be constrained, not perfected. Keyfiles, hardware-backed authentication, and phishing-resistant MFA are examples of compensating controls designed around the assumption that passwords will eventually fail.

Conclusion

Passwords get hacked for predictable, well-understood reasons. They are reused, stolen through phishing, harvested by malware, exposed in breaches, and exploited by automated attacks. In most cases, no sophisticated hacking is required. Attackers simply take advantage of how passwords are used in the real world.

The key takeaway is that password compromise is not an exception—it is an expected outcome over time. Stronger passwords help, but they do not solve reuse, phishing, or device compromise. Additional controls such as unique credentials, multi-factor authentication, secure storage, and local-first security designs are necessary to limit damage when passwords fail.

Understanding these dynamics allows individuals and organizations to make better decisions. Instead of asking how to create the perfect password, the more useful question is how to reduce reliance on passwords altogether and contain the harm when they are inevitably exposed.